It’s time to dispel the myth of Mayberry.

2016 was a violent year for all law enforcement.

For those in small towns and remote places, the impact was disturbing and disproportionate.

The very first officer killed in 2016 was ambushed in a tiny Ohio town; the very last officer to fall died responding to a domestic disturbance in an even smaller Pennsylvania village.

In between were dozens of other rural officers, broken and killed by risks seldom acknowledged by a public convinced that “nothing ever happens in small towns.”

In the real world numbers,not headlines, tell the story, and LESMA’s Officers Shot in 2016 spreadsheet has the numbers.

(LESMA tracks officers shot as a measurable segment of attacks against officers. Please don’t read anything more into that choice than simplicity of documentation.)

In 2016:

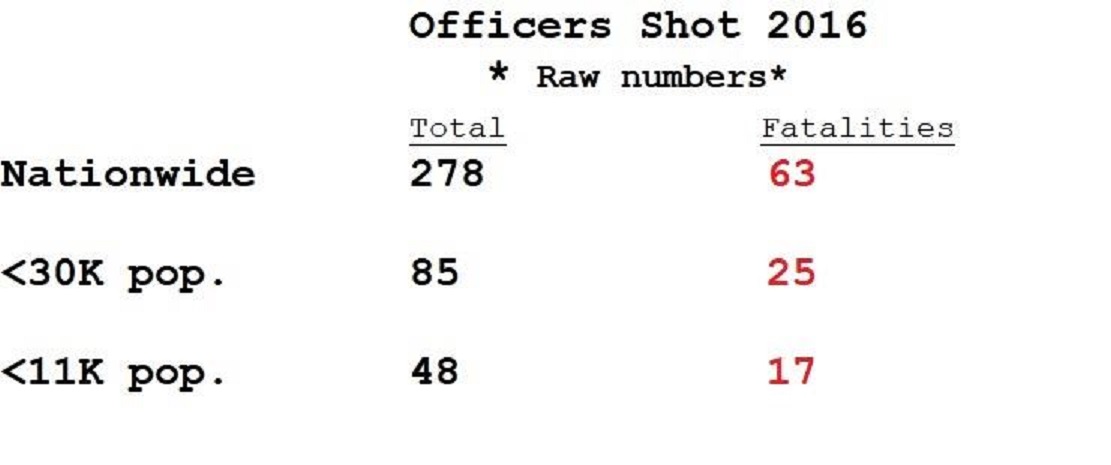

*278 officers were shot.

*85 of those officers were shot in areas with a population of less than 30,000 residents.

*48 of the officers were shot in areas with fewer than 11,000 residents, the smallest area being Hesston, PA (pop. 631), where a Pennsylvania state police officer fell at the very end of the year.

A quick look at fatalities:

A total of 278 officers were shot nationwide; 63 of them died.

85 officers were shot in areas with residents numbering <30k ; 25 of them died.

In areas with population <11K, 48 officers were shot, and 17 of those were fatalities.

Raw numbers don’t really mean anything. What story do the numbers tell? Break them down, and we will see:

As the numbers above demonstrate, when the town gets smaller, the fatality rate for wounded officers gets higher–a lot higher.

Officers from small towns and rural areas face substantial risk, with fewer resources and certainly, less press about the dangers of the job they do.

And there’s the story; I’ve suspected it for a long time, but this is the first time I’ve had an entire year of data to interpret.

The next question has to be: Why?

As far as I know, no one has ever asked that and looked at the reasons behind it. All I can offer is speculation, based on my personal observations and knowledge of rural areas.

It’s common for rural officers to work alone, with backup far away. That translates to : no one to provide cover, and no one to help a downed officer, pack his wounds, help with a tourniquet, or call for aid if he cannot.

It’s common for rural officers to work where budget constraints mean working without safety equipment that’s taken for granted in cities:

ballistic armor, patrol rifles that allow distance between suspect and officer, tourniquets, rifle plates , even reliable radio coverage.

Rural residents and elected officials tend to talk a good talk about law and order, and ‘backing the blue’.

The harsh fact is that talk isn’t support.

Encouraging words and blue porch lights, while welcome and appreciated, don’t provide equipment, training or additional patrol positions.

Self-reliant country attitudes frequently coincide with resistance to adequate tax bases and growth of government agencies that allow for realistic coverage.

Rural areas and small towns rarely have rapid access to sophisticated trauma care.

Some don’t even have small, critical access hospitals that can stabilize a wounded officer for transfer to higher levels of care; when they do,getting to them often involves long waits, and longer transports.

Time and distance are the enemy of the Golden Hour.

Again, I cannot prove that this directly contributes to increased mortality rates, but it seems a reasonable conclusion to make.

When an officer like the detective shot and critically wounded in Douglas County, CO, can be in a trauma center within minutes–and survive–but a Navajo officer shot early in 2017 lay helpless until a passerby found him, and struggled without cellphone service to get him medical aid , it’s a hard comparison to avoid.

I can’t prove a connection, but I would like to find out if more rural officers are shot with rifles than are urban officers. Country life and rifles go together in a way they can’t in a city.

Handguns are easily concealed, and widely available in urban settings. Long guns? Not so much.

It’s hard to stick a rifle down your pants, and it won’t fit in your pocket.

In rural areas, rifles are like pickup trucks: plentiful, common and not worth a second look, let alone suspicion–

and soft armor won’t stop them.

Maybe eventually we can start tracking weapons used in critical incidents, but right now that data simply isn’t available to me.

My favorite question is, “Then what?”

For this problem , ‘then what’ is: get the word out.

Mayberry IS a myth.

Start by sharing this information with department heads, county and municipal administrators and news agencies to confirm that YOU ARE facing real and present threat, that deserves to be addressed and mitigated.

Administrative and reporting decisions are currently based on idealistic and outdated impressions of what “rural” means.

Data is much, much harder to dispute than an idea.

A case needs to be made, nationwide, that law enforcement agencies in every place and at every level have worth and dignity, and deserve to be trained, equipped and staffed appropriately for the jobs they are asked to do.

Failure to do so is a decision in itself.

It is also a moral and ethical choice–the wrong one.

The real problem impeding these solutions isn’t budget, it’s will.

That’s even harder to overcome, in some ways, than figuring out funding streams or accessing training.

Asking communities to help their officers address these risks requires the citizens to admit publicly that their safe, quiet little town isn’t really what they wish it to be.

It means giving up false, fuzzy facades of the ‘good old days’–which weren’t really all that ideal anyway (but that’s another blog post).

Of the 63 officers shot so far in 2017, 26 of them were in places smaller than 30,000 residents, including five of the 13 fatalities.

If no one else is looking at that number, then we have to make them see.

News coverage is deceiving: large urban areas are reported as threatening and scary.

“The country” is idealized and Disneyfied.

This is real life, and you live it.

Mayberry never was a real place.

#Mayberrysamyth

Sobering information. Safety equipment, maybe. I am fortunate in that our agency provides vests and rifles. Response time and quality of emergency medical care could certainly play a factor. Depending on where the incident goes down, it could take a while for EMS to arrive on scene. Personally, when I know backup and medical care is a long ways away, my spidy sense grabs an extra gear. When it gets down to the nitty gritty, officers bear the brunt of responsibility for safety habits and gear.

LikeLike

Great article

LikeLike

Thank you ; glad to have you here.I hope these concrete numbers can be of help with your agencies' decision making.

LikeLike